In 1971, Guy Lafleur faced a St. Catharines team in a Memorial Cup playoff series that never finished

Published April 22, 2022 at 10:50 pm

The death of hockey legend Guy Lafleur has brought forth all manner of emotions from people who have hockey, Canada and Quebec in their hearts.

While time is said to heal all wounds, and it has been 51 years, hockey lovers of a certain vintage in St. Catharines and the Niagara Region might have a unique memory involving the superstar, who was known as Le Blond Démon and The Flower. Lafleur, who died Friday at age 70, earned lasting flame as a transcedent ace scorer in a sport that is known for trying to drag down its brightest lights.

Some credit the Lafleur-led Montreal Canadiens teams that won four consecutive Stanley Cups from 1976 to ’79 with saving hockey after the Philadelphia Flyers of Broad Street Bullies infamy won back-to-back titles with a system that often involved intimidation and thuggery.

A few years earlier, though, a greater ugliness, one of the nastiest chapters in the political history of Canada, scuttled a Memorial Cup playoff series. In 1971, a 19-year-old Lafleur was a junior hockey wunderkind with the Quebec Remparts, while the St. Catharines Black Hawks, with their own future hall of fame forward in Marcel Dionne, met in a Memorial Cup semifinal playoff series.

Forfeited

The cross-culture clash, though, came in the wake the FLQ Crisis in Quebec that had led then-prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau to invoke the War Measures Act. And while many people prefer, or pretend, that sports is a politics-free space, cultural and linguistic tensions boiled over and made it impossible to finish the series.

With justifiable fears about their safety in Quebec, the Black Hawks forfeited the Eastern Canada championship series after five games. Quebec was ahead 3-2. Lafleur, et al., then swept the Edmonton Oil Kings, the Western champs, 2-0 in a best-of-three series.

The series had been marred by controversy over officiating, fights, and fans endangering player safety by throwing objects at them during two games in Quebec City. Reports surfaced later that the militant separatist group Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) made threats against St. Catharines players.

A fair bit of tumult in terms of the structure of major junior hockey also played into it. A half-century ago, there was no corporate parent such as the Canadian Hockey League tying together Ontario, Quebec and Western leagues. There were no triple-A youth leagues or summer hockey that had boys and girls criss-crossing North America from the time they were nine years old, helping prospects become acquainted with each other well before they came of age for junior.

Junior leagues were shifting from being sponsored by NHL teams to being stand-alone teams. The NHL, long after the other three big North American sports leagues had done so, adopted a true entry draft in 1969. That was also the same year that the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League was organized.

The Ontario Hockey Association, forerunner to the OHL, was considered the highest level of competition for teenaged prospects anywhere east of Manitoba. The calibre of junior puck in Quebec was so lightly regarded that the Montreal Jr. Canadiens franchise played in the OHA. Dionne, of Drummondville, Que., had moved to play in St. Catharines in 1968 to showcase his skills for a future employer that could have been any of the 12 NHL teams at that time.

His parents faked a separation so Dionne could get his release to go play in Ontario. Or so the story went.

While the hockey hierarchy in Quebec had failed to keep Dionne in the fold, it was a point of pride that Lafleur had cast his lot with the Remparts. The blond forward from the Ottawa River pulp-and-paper town of Thurso, Que., had been hyped as a ‘next one’ since his adolescence. In the Q’s first season, he scored 103 goals. In the Memorial Cup playdowns, through, the Remparts were swept by — chip on the shoulder alert — Montreal from the OHA, led by future Buffalo Sabres great Gilbert Perreault.

Worlds colliding

In 1970-71, in the lead-up to the showdown with St. Catharines, Lafleur scored 130 goals and 209 points over 62 regular-season games — two goals and one assist per game. The stigma of Quebec junior hockey as second-best would have still been out there after the sweep against Montreal the year prior.

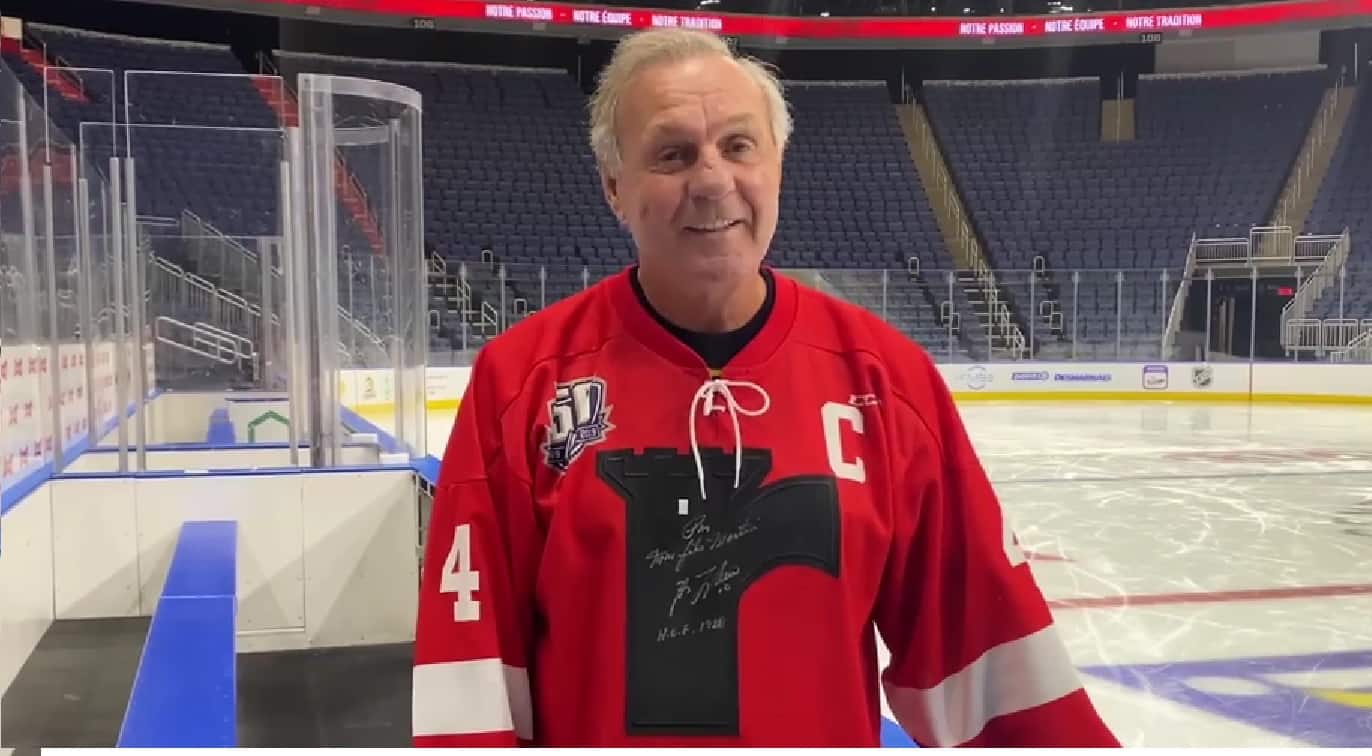

Lafleur wore No. 4 in junior, just like Canadiens captain Jean Béliveau. His celebrity in Quebec was such that he was given the licence plate 4G-4444.

No. 4, which Lafleur took to emulate Canadiens captain Jean Béliveau, is now retired through the QMJHL.

Over in Ontario, Dionne averaged more than three points per contest for St. Catharines — 62 goals and 143 points over 46 games. The Black Hawks peaked in the playoffs, dropping just two games across three series on their way to the J. Ross Robertson Cup.

There was also some hardball afoot in the hockey boardrooms. The Memorial Cup had always come down to an East-West showdown. The creation of the first major junior league, the Western Canada Hockey League (now Western Hockey League, or WHL) in 1966 had upended that tradition. Before the 1970-71 season, the OHA said the Eastern champion would not play the Western champion.

‘Wild’ Bill Hunter, the coach, general manager and proprietor of the aforementioned Edmonton Oil Kings from the WCHL, went all in on the rhetoric. Hunter — one of the sport’s all-time disruptors, who would soon help start the World Hockey Assocation, and would almost succeed in moving the St. Louis Blues to Saskatoon in 1983 — called on the original PM Trudeau to resolve the impasse.

“If the prime minister wants to do something right for the west for a change, he’ll use the War Measures Act to enforce a Memorial Cup final,” Hunter reportedly said some time in 1970.

Speaking of that other national calamity, the FLQ Crisis came to a head in the fall of ’70. In October, members of the FLQ kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross. A cell of the FLQ also kidnapped and murdered Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte.

That led to Trudeau imposing the War Measures Act for the only time in Canadian history outside of the two world wars.

(The act has since been replaced by the Emergencies Act, which was not used until February of this year when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau imposed, allowing police officers to clear anti-public health and anti-democracy illegal blockades in downtown Ottawa and at border crossings that were enacted by supporters of the Freedom Convoy 2022.)

So that was no doubt prologue to the Lafleur-led Remparts from the upstart QMJHL met St. Catharines. All of Canada’s long-running tensions — French-English, East-West, how to fund and create our own sports and games — were swirling.

It is not hard to empathize with how people got caught up in it. The Black Hawks, just by existing and repping Ontario with two Québécois standouts in 19-year-old Dionne and 18-year-old Montrealer Pierre Guite, stood in for the Rest of Canada.

The series opened in St. Catharines, at the Garden City Arena, which is now winding down its useful life. Quebec and St. Catharines split the first two games. It likely did not help keep the focus on hockey that Remparts coach Maurice Filion called the game officials anti-Francophone.

Games 3 and 4 were in the Colisée in Quebec. St. Catharines received over three-quarters of the 102 penalty minutes that were whistled as the Remparts won Game 3 to take the series lead.

Crowd control was not so much of a thing 50 years ago. Game 4 got out of hand on the scoreboard first, with Lafleur scoring a hat trick in a 6-1 Quebec win. St. Catharines, as a team does in the playoffs to show that they are not yet beaten, turned their physical play up a notch to send a message for the next contest. There were fights on the ice. The partisan crowd let loose with, according to multiple accounts, a fusillade of eggs, golf balls, potatoes, tomatoes and bolts that had been unscrewed from the bottom of their seats.

“It was a nightmare,” Black Hawks forward Bobby MacMillan, who went on to a long-term NHL playing career and also became a scout, told the Calgary Herald in 2010. “A riot, basically.”

Police officers had to escort St. Catharines to their dressing room. And while Quebec was one win from clinching the series, fans spilled out of the arena and rocked the Black Hawks’ team bus. Accounts say players dove to the floor for their safety.

The teams would play one more game. Game 5 was moved to Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, and St. Catharines won to extend the series, if only nominally.

Quebec refused to shift Game 6 to a neutral site. And that was that, as St. Catharines voted not to return and forfeit.

The Remparts, though, still wanted to, as Reggie Dunlop would say years later in “Slap Shot,” win it clean. A short series was arranged with Edmonton. By accounts the Colisée crowd were gracious and welcoming to the westerners as Lafleur and their heroes romped to the Memorial Cup, in a coup for the new QMJHL.

Aftermath

High-level hockey in St. Catharines has been through a few iterations since that ’71 season. The Black Hawks won the OHA title again in 1974, but by then they were vying for hearts and eyeballs with the nearby Sabres, and struggling to keep up attendance. The franchise eventually moved to Niagara Falls in 1976. A replacement team, the St. Catharines Fincups, also couldn’t get traction and moved in a trice.

While the title and location of an OHL team can change, memories and history are rooted to a time and place. St. Catharines’ current OHL team, the Niagara IceDogs, have recognized their puck-chasing predecessors. In 2019, the IceDogs raised banners at the Meridian Centre to commemorate the ’71 and ’74 Black Hawks. They also sport Chicago-style red, black and white uniforms.

And Dionne has kept ties in the area. For over a decade, the hall of famer and his family operated the Blue Line Diner in Niagara Falls, with a memorabilia store next door. It became a popular breakfast spot before closing in 2020 during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Anyone who has ever gone down a HockeyDB rabbithole knows that Lafleur and Dionne were drafted 1-2 in the NHL draft, and went on to hall of fame careers. (A few trivia nuts might know that St. Catharines’ other Quebecer, Guite, won a championship as a pro. helping the Quebec Nordiques win the World Hockey Association’s Avco World Trophy in 1977.)

The legacy of that ’71 debacle might be tied to something much larger, and much better remembered. The FLQ Crisis, which spilled into hockey, was also a catalyst for hockey becoming a national unifier just a year later.

Powerbrokers in Canadian hockey had wanted to create an NHL vs. Soviet Union national team showdown for years, as a hockey take-off on soccer’s World Cup. The events in October 1970 also motivated Pierre Elliott Trudeau to try to foster national unity. He also wanted to improve Canada-Soviet relations.

In May 1971, Trudeau spent two weeks on a state visit to the then-USSR. On that trip, he met with the No. 2 man in Moscow, Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin. They met again later that year in Toronto. Some of their talk involved hockey. That was one part of opening the door at the state level to finalizing terms for the famed 1972 Summit Series, whose 50th anniversary will be marked later this year.

And, of course, when Paul Henderson scored with 34 seconds left in Game 8 in Moscow, the first teammate to hug him was Yvan Cournoyer. An Ontario-born Toronto Maple Leaf, being embraced by a Quebecer from Les Canadiens.

inNiagaraRegion's Editorial Standards and Policies